Last week, I wrote about the potential side-effects of pseudo-authentic assessments and offered some suggestions on how we might be able to shift our practice more towards true authenticity.

I remember asking my wife once about fashion shows and why the models wear these ludicrous outfits that you would never actually see in real life. She explained to me that a fashion show was like a hyper-exaggerated example of what we might see in fashion reality that season. If a model was wearing, say, an outfit that looked like it had been stolen right off the body of an ostrich, that might indicate that feathers might be featured in fashion that season.

Where am I going with this? Well, I love to philosophize and think of big grand ideas. Over my last two years working as a coordinator, I had the latitude to do this. I saw my role as the fashion designer – challenging my colleges with idyllic suggestions, with the hope that some watered down version of my original provocation might manifest itself in practice. However, this year, with the opportunity to move back into the classroom, I

am challenging myself to put my money where my mouth is.

I am fortunate in that my school has entrusted me to develop an MYP Media program. This means that I have a little bit of room to try to apply some of the ideas I had been playing around with as a coordinator, but this time in my own practice.

With no doubt, the manifestation of principles into practice is amongst the most challenging aspect of teaching for many practitioners, myself included. Over the past eighteen months, I have used this space to share my ideas and discoveries.

This is an attempt to share what I have tried thus far in my classroom, in an honest effort to support student learning by allowing the maximum amount of autonomy that I possibly can, within a system that, in my opinion, creates many barriers towards students voice and agency.

1. Building the course outline:

During the first week of school, I presented my students with the course outline for our class. It was a blank piece of paper with four sections:

- What do you already know?

- What do you want to learn?

- What do you not want to learn?

- What are you excited to try and do this year?

Students worked, first individually, then in small groups, then as a whole class to develop and consolidate their desired program of learning.

What to know what to teach? Just ask your students.

2. Listening to my students, despite my own agenda:

Initially, I wanted to kick off the year by facilitating a collaborative unit-planning process with my students¹ – allowing them the opportunity to select key and related concepts, develop a statement of inquiry and develop assessment tasks.

However, upon beginning this process, my students commented to me that it was too confusing and they felt they did not have a solid enough understanding of the course expectations to plan the unit. They asked if I could plan the first one, as an exemplar, and then they would feel more equipped to plan subsequent units.

This was a huge learning moment for me – I wanted my students to plan everything this year. What to do? Force them to follow my agenda? That would be no different than forcing them to learn pre-determined content. I opened my mind to the fact that student voice is student voice, even if that means they want me to do a little bit more of the driving to start the year. When I took a big step back from the attachment to my vision, I realized this was an incredibly logical and insightful request.

3. Learning “The Rules of the Game”

Let’s face it – in it’s current iteration, school is a game. If you teach within the MYP, you know that this is a game with many rules – Objectives, Criteria, ATL Skills etc. – there are a lot of ins and outs that are crucial for students to learn if they are going to take control over their own learning, while still operating within the rules of the game.

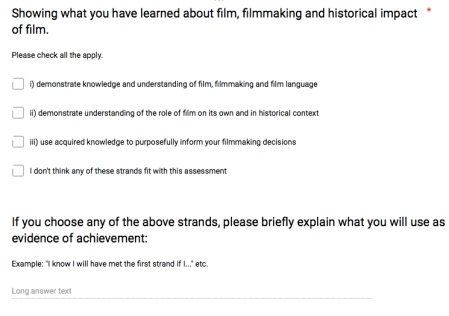

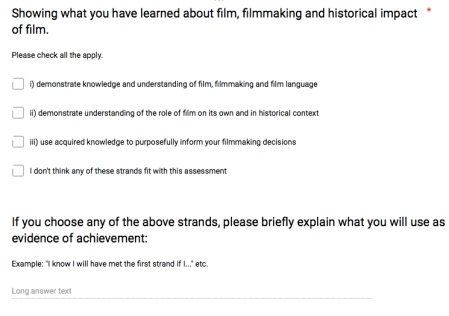

In order to learn the rules, we spent some time translating the MYP’s Arts Objectives into student-friendly, media-specific language. We then plugged these objectives into SeeSaw, our online student portfolio system, so that when students feel they want to be assessed on their learning, they can upload something to SeeSaw and choose the Objectives for which they would like to be assessed.

Knowing the rules of the assessment game can empower students to take control of how they demonstrate their learning.

4. Allowing students to teach each other

Content knowledge is so easy to access online that there isn’t reason for me to do much in the way of traditional “stand and deliver” teaching. In order for students to negotiate the ways in which directors create great scenes, they used blogs and YouTube videos to develop an understanding of some of the terminology and concepts associated with filmmaking. From here, the students created workshops, mini-lessons, handouts and Kahoot quizzes in order to ensure that their fellow learners were up to speed. My job in this tended to focus on supporting students in collaborative and empathy building skills, while at the same time empowering the students in my class to be confident in their learning take on the role of lead-learner. From here, I would circulate to fill in any gaps in knowledge and correct misconceptions. However, the best aspect of this process was getting to assert myself in the learning process, as a learner. I joined groups, did projects, took quizzes and got in trouble for talking out of turn. This allowed me not only to model the practices of learning and collaboration, but also allowed me to learn new skills from my students, hopefully flattening some of the power dynamics inherent in a classroom setting.

My students taught me how to become a green smoke breathing dragon!

5. Allowing students to design the assessments

The first piece of inquiry that students said they were interested in learning was a little bit of film history and a little bit about the ways in which directors create scenes. In order to learn this, we found ourselves using a great deal of film scene analysis. It was only logical, my students concluded, that for our first assessment, we should create an analysis of our own in order to demonstrate our knowledge and understanding.

Once we had decided on the task, we used a Google Form to collect data on which of the Assessment Objectives we should be connecting to this assessment. We also used the same form to develop the “task specific” or “how will you know you have been successful?” language of the rubric. We decided to use the single-point rubric method, as it is more efficient to create and easier to interpret.

A simple Google Form can be an empower students to design assessment.

6. Forced vs. Sought feedback

One of the best and loveliest edu-bloggers out there has a fantastic post about the difference between forced and sought feedback. My students and I looked into this idea and decided that when we are truly engaged, we don’t need to be told to get feedback – we naturally seek it out. We also discussed that feedback can come in several forms: from a teacher, from an expert, from a friend, through use of an exemplar etc. Throughout their scene analysis design I saw students seeking a variety of feedback types from a variety of experts in the room and online. The biggest win from my perspective was the students’ articulating specially the aspect of their project for which they wanted to receive feedback. “Can you listen to my voiceover and let me know if the audio is clean?”, “Do you think the freeze frame here is too long?”, “What’s that YouTube channel that has really good examples of film analyses called?”. These questions and more showed that students were aware of the areas that they were less than confident in, but more importantly, they were aware of strategies to get support.

7. Triangulation of assessment and empowering students to give themselves grades

I’m certainly not sold on grades and I’m still unsure of why they are such a big part of a program that claims to be focused on skill development and conceptual understanding. It just seems counterintuitive to have all of these great conversations about learning, only to eventually boil that down to a number that oversimplifies and disrespects the entire learning process.

Nonetheless, these are the rules of the game and the game we must play. To this end, when my students were finished their analysis, they uploaded their work to SeeSaw and I took a look in order to give them specific feedback based around the individual assessment strands students identified earlier. From here, students shared their work with a peer, who gave them feedback, just as I did. Finally, students gave themselves feedback, using the same system. With all three of these data points available, students then synthesized the different perspectives in order to select a grade for each of these objectives. These grades and the students’ self-assessment feedback then went straight into ManageBac and resulted in at least half a dozen students going into shock that they were “allowed” to be active participants in their own assessment².

8. Getting better

Naturally, there were some students in my class who, upon going through the entire assessment process, realized that they perhaps did not manage their time or effort to the best of their abilities. Without a doubt, I think it is imperative that when students identify mistakes, that they be given the opportunity to use this reflection as a learning opportunity. So when these students came to me wondering if they could improve their final product and reassess themselves, the answer was an enthusiastic “yes!”. Giving students the opportunity to identify and correct mistakes let’s them know that the learning process is never over and that learning and improvement take priority over demonstration.

***

Looking back on the first quarter of the year, I am grateful to have had the opportunity to try to put some of these ideas into practice. I know that this certainly is not the epitome of agentic learning, nor is it close the ultimate vision I have for the learning atmosphere in my class, or in schools in general – however, it is a start and a start that I’m looking to build on in the coming months.

Along this journey if you’re an MYP teacher and would like to collaborate around strategies for increasing student agency, please connect with me on Twitter @bondclegg – I’d love to keep the conversations going!

¹ While Principles into Practice certainly emphasizes the role of the teacher in planning units, this is a place where I think they’ve missed the mark and have chosen to delicately side-step this practice at some point this year…I’ll let you know how it goes!

² If you’d like to check out some of my work on Student-driven Assessment, please click this link.